Nicolas Maduro is the president of Venezuela. He took power in 2013 and has since effectively driven the country to the brink of economic catastrophe. Violence, food shortages, unemployment and political turmoil had led to more than 3.4 million Venezuelans fleeing the country.

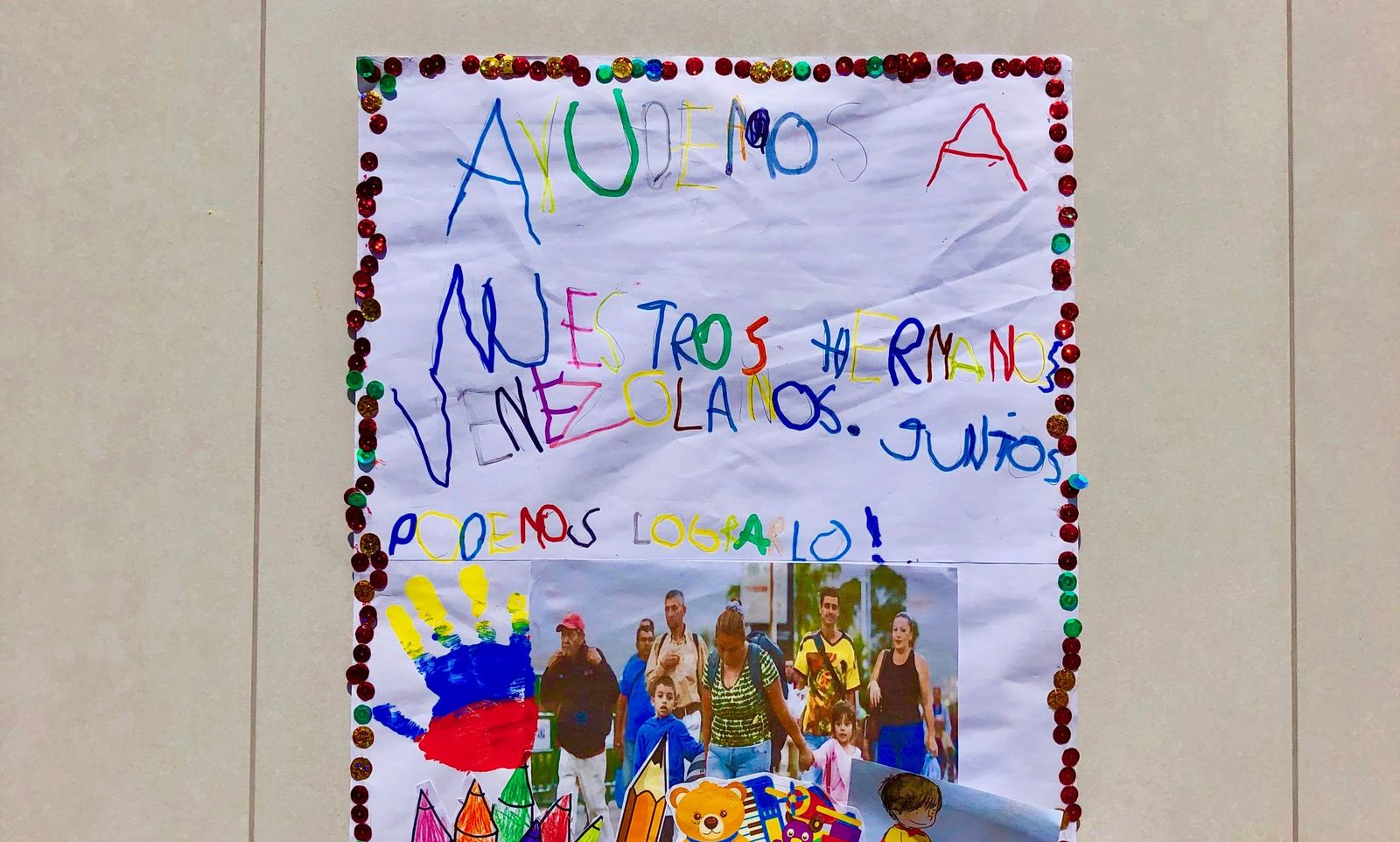

South American countries are feeling the pressure of the Venezuelan migrant crisis. My adopted country of Peru has taken in the second largest number of migrants. I work and live in the city of Tacna; a border city with just over 300,000 residents. Tacna sits 30 kilometers from the Chilean border. Chileans and Peruvians cross the border each day for work or shopping. For many Venezuelans, Tacna is another stop on their journey south. Chile is an economic powerhouse where jobs are good and the standard of living is higher than here in Peru. Additionally, the Chilean government has strong support systems in place for those who fall beneath the poverty line, including refugees. In Peru, there isn’t much governmental support for the poor.

At the end of June, in an effort to control the number of Venezuelans entering Chile, the Chilean government began requiring that all Venezuelans obtain a visa in order to enter the country. The small city of Tacna quickly became the site of a humanitarian crisis as thousands of Venezuelans lined up outside the Chilean consulate, often spending the night in tents and without food just to receive a visa.

In August, at the tail end of the crisis, I began volunteering as a Jesuit Volunteer with the Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes (SJM). In normal times, SJM would attend to immigrants needing support in establishing themselves in Tacna. However, in light of the Venezuelan crisis, they’ve begun working almost around the clock to help migrants sort out the confusing immigration process, take them to doctors’ appointments, and make sure they arrive safely and well-fed to shelters each night.

I’m incredibly blessed to work with such a dedicated group of people. It seems that no matter how difficult the situation, they know just exactly what to do. Through SJM I’ve been able to understand better the depth of the crisis. I’ve gotten the chance to interact with many Venezuelans who have decided to stay in Tacna. The situation isn’t perfect here; Venezuelans face a lot of discrimination and job insecurity. Private Facebook groups empower ill-informed Tacnenos who want to rid the city of Venezuelans--sound familiar?

“We’re relieved, we feel more united as a family. In Venezuela, we had barely anything,” a Venezuelan woman who arrived in Tacna with her family in August told me. Tacna is not without its flaws, but there is hope for a better future.